7 #ProTips for Determining Your Business’ Marketing Budget

Struggling with managing your business marketing budget? You're not alone. These are the principles that guide our approach.

Determining your business’ advertising budget depends on a variety of factors including the business’ growth stage, resources available, and even owners’ preferences. While there are many ways to approach budgeting, this is the framework I’ve found helpful.

- ProTip #1: Avoid the budget “fallacy”

- ProTip #2: Every channel is different

- ProTip #3: Every campaign is different

- ProTip #4: Channel/campaign combos change

- ProTip #5: Model before you buy

- ProTip #6: Plan to lose, before you win

- ProTip #7. Monitor & Adapt

Want the slides? Get them here.

ProTip #1: Avoid the “budget” fallacy

Before we get started down this path of putting together an advertising budget, I want to remove some “head trash” and misconceptions that most of us have when it comes to budgeting. Starting with the word “budget.”

The problem with the “budget” frame is that it assumes that marketing is, de facto, an expense. That’s because it looks at the “cost” side of the equation, but not necessarily at the revenue side of the equation. Unless costs & revenue are married, you’re never going to be quite sure whether your marketing is successful or not. Or whether your advertising is successful or not.

There’s a great quote by John Wanamaker that frames how most of us think about advertising:

“Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.”

– John Wanamaker

Fortunately, technology has come a long way since the early 1900s, so it’s much easier to tell which half is “wasted.” Or, more likely, misallocated.

Yet, because we only look at the “expense” or “cost” side (and don’t – or don’t know how to measure – ) the revenue side, we miss out on good opportunities while wasting resources on bad ones. When we market by “gut,” and only have “cost” as a concrete measuring stick, we’re much more likely to fret about budget. And far less likely to have profitable marketing.

So, here’s my general maxim:

If your marketing strategy is losing money, or if you’re not sure, stop doing it. Otherwise, keep doing it.

This maxim forces focus on both the cost and revenue side of the question, which sets us up for success. Or, at the very least, it prompts us to figure out how to think about our marketing efforts, so we can start to fill in the variables we’re not sure about.

ProTip #2: Recognize that every channel is different

The second thing to recognize before you put together any kind of a budget is that every channel is different.

When I went to business school, we talked about the four P’s of marketing. Those are:

- Product – what you’re selling

- Price – what you’re charging

- Place – where you’re distributing your product/service

- Promotion – how you’re communicating your message

This model is academically debated, but one of the things I see in practice is that most people conflate marketing and promotion. In other words, if they’re advertising, then they’re “marketing.”However, advertising is only one component of marketing. I’d go further and argue it’s actually only one component of “promotion.”

Very few people I talk to seriously consider the place component of their marketing mix. Yet, promoting in the wrong place is almost always going to be unproductive and unprofitable.

Getting Place Right

I think one of the reasons people don’t think much about “place” is because many “marketing” agencies tend to be good at one tactic or another. One channel or another. And, so the myth of confusing “place” with “promotion” persists. So, perhaps a concrete example helps.Have you ever been to Home Depot or Lowe’s and seen a “home services” contractor there selling windows or countertops or the like?Ever wonder why they’re there?

Bingo. Because that’s where the customers are.

Nearly every person walking into a Home Depot or Lowe’s is fixing or renovation something at home. So these contractors are there, precisely where the customers are, which dramatically increases the probability of generating sales.

Why fish in a dry or uncertain pond, if you have access to a fertile one?

Wherever your customers are, go there.

Of course, this requires you to know who your customers are and where they are. But, if you don’t know those things, you’re probably not ready to invest much in promotion.

Analyze Prospective Channels

It’s important to recognize that every channel has its strengths and its weaknesses. So, one of the things I suggest you do before you put together any kind of campaign or budget idea is to do a quick SWOT analysis for the different channels where you’re considering an investment.

That means reviewing 4 things related to the channel:

- Strengths – e.g., you know the channel well, you like it, etc.

- Weaknesses – e.g., it’s expensive, hard to measure, you don’t know how to use it

- Opportunity – e.g., the potential market size of the channel, it’s productivity relative to your ideal customer

- Threats/obstacles – e.g., the channel is diluted, hard to get access to, etc.

For example, if you’re the kind of person who really likes people and likes to “glad hand,” then find channels that maybe play to that strength. For example, networking groups or trade shows. Of course, a weakness of that kind of channel is, in the Covid-19 world, it likely doesn’t exist much anymore. But even at the best of times, it’s only as productive as the time you’re putting into it.

Also, the opportunity is bound by the size of the crowd or number of people you can directly interact with. And, depending on the venue, the threat of a worthy competitor being within view of the prospect is also possible.

Digital channels have a different SWOT configuration, not the least of which may be your comfort using them.

ProTip #3: Every campaign is different

The third thing I’d advise is to recognize that every campaign is different. Because different channels have different SWOT values to different people with different businesses, some campaigns are going to be more effective than others. For example, many of our competitors prefer to advertise via PPC, while I prefer to meet customers and talk to them.

My current SWOT configuration prioritizes relationships.

It’s not better or worse, just different.

Start with a channel’s”purpose”

Before campaign planning, it’s really important to think about that channel’s purpose. After all, channels exist and grew to fulfill some purpose somewhere. For example chambers of commerce do advocacy and attract in person connection. BNI exists to share referrals within a small, trusted cohort. Facebook exists exists to facilitate interpersonal digital connection. And Google exists to match people looking for information with people who have it.

Recognizing a channel’s purpose gives you a lens into how that channel can best be used or optimized.

For example, if you need customers right now, and you’ve got some money, Google Search might be a great channel to explore because it marries people searching for your service with people like you, who have a service to offer.

Conversely, if you’re bringing a new product to market and there’s little or no corollary that people are searching for, try something else. Maybe a display, Facebook, or Instagram ad. If you have content to share, try Taboola. If you really want to emphasize that your business has a personal touch, then take advantage of networking or trade shows or whatever.

By recognizing that different channels have different purposes and different strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and obstacles, you can really start to put together a framework for how to think about budgeting for that channel and tempering your expectations, accordingly.

More than money

Another mistake we see people make when they consider budgeting, is they only think about money. This happens most often when money is tight.

The reality is that all campaigns require four key resources. They are:

- Time – to put them together, run them and measure them.

- Effort – yours or someone else’s

- Energy – which varies depending on how fertile the channel is

- Money – the capital required to communicate the message and/or take care of 1-3 above.

Going back to some concrete examples, something like a BNI is going to require time every week, but probably not a lot of money (as far as advertising dollars can go). Depending on when your group meets, it could require a lot of energy. The group I was a part of met early, and I prefered to dedicate that energy during those hours to other tasks. It may also require a lot of effort to drum up referrals every week or two, unless you’re a natural connector.

However, something like Facebook advertising or Google Search Ads could get very expensive very quickly. They also require a lot of effort to learn how to do well, plus they take time to optimize.

Ultimately, you want to assess your 4 key resources, your business’ needs & goals, your channel SWOT, and then you can start putting together a campaign that makes sense for your budget.

ProTip #4: Channel/campaign combos change

The Fourth thing to recognize is that campaign and channel combinations will change as your resource portfolio changes. As your business grows, so will the types and scope of your campaigns. For example, early stage local or service businesses almost always have to be carried on the back of the owner. He or she will network, drum up referrals, and is the principle salesperson.

It’s not always the case, but pretty often is.

As the company grows and has cash to deploy, Google Search is often a wise next step. Because Google marries searchers with people who want to be found, it can quickly become a productive channel if well-optimized (and a HUGE HUGE HUGE waste of money, if not. Note: if you aren’t investing in landing page optimization, please don’t waste money on Google Ads. End note.)

As business grows, then display or social media ads start to become more important. Again, it depends a lot on the particulars, but I’ve found this to be a general rule-of-thumb for most small, local, service-based businesses.

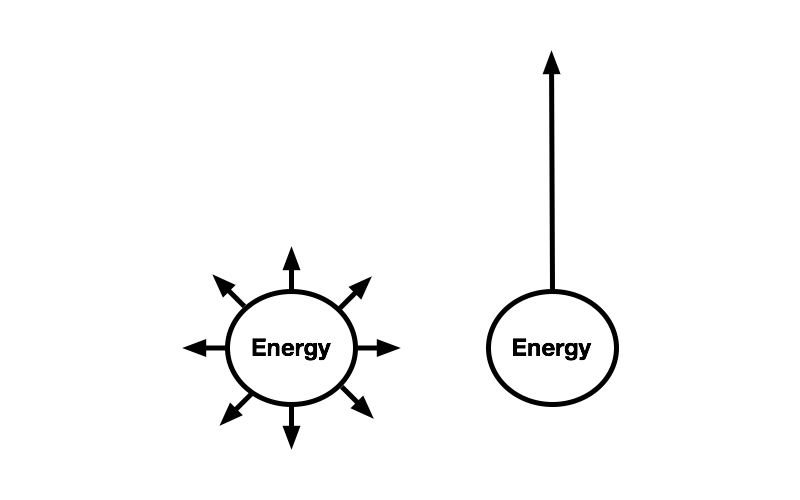

Either way, focus is key. I recall seeing a graphic in Greg McKeown’s “Essentialism” that looked like this:

I think he was talking about the difference between a light bulb and a laser. With the same wattage, one will put a hole in you and the other doesn’t. The difference is focused energy versus dispersed energy.

With the Internet, this is especially important. Every channel is so focused that an ad that hits on Facebook will likely flounder on Google. I’m still not sure anyone knows the value of advertising on Twitter. But, I digress.

One of the temptations people have when putting together a marketing budget is to try and think broadly, rather than thinking in terms of focused, narrow channel/campaign objectives. Often, this is accompanied with a feeling they should be taking advantage of the “hot tactic” of the day.

Which is more valuable – time, or money?

One of my budgeting principles is to ‘start with no.’ This is partially because we don’t yet have a lot of discretionary cash to focus on channel dispersion and optimization.

Most of our customer’s don’t either.

Big companies can afford to be ubiquitious, but small ones must be strategic. Small – or resource-strapped – businesses would to better to budget like guerillas than like Fortune 500s. Hence, the focus on “place” over “promotion.”

Again, while every business is going to be a little bit different based on their resource portfolio, for young businesses, your money is more valuable than your time. For growing or bigger businesses, that is inverted. For small businesses, where money is dear, you can’t afford to ‘waste’ a lot on broad campaigns with low conversion value. Focused messaging to focused markets in focused channels will win the day.

However, as you grow, you have enough money to explore markets and buy time. That means investing in channel experts who can help you find your ideal customers on different channels.

But, you should expect to use money to pay for those services while you keep existing customers satisfied.

ProTip #5: Model before you buy

In order to avoid the budget fallacy I talked about before, you have to know if your campaigns are profitable. And so I tend to think that you should model campaigns before investing in them. The key factors to consider when you’re putting together a model are:

- Key product information,

- Key channel assumptions,

- Key sales metrics, and

- Customer value

The key subcomponents I think through are:

Product Information

Product information concerns things like:

- Average unit revenue: how much, on average, selling one item/good/service brings in

- Average unit costs: how much, on average, it takes to produce one item/good/service

- Gross Profit/unit: revenue – cost. I tend to focus on gross margin because it’s usually less flexible than net profit margins. It’s usually easier to trim overhead than negotiate lower prices from suppliers.

- Average profit margin: This is a good thing to track so you know how well you’re competing. Plus, cash from gross margins funds the rest of everything you do.

Channel Metrics

Channel metrics will vary by channel, but I think of these things as how much awareness you expect to generate and how much of that awareness turns into qualified engagement. For example, if my channel is inside sales, the number of calls made (where someone answered) might be an “awareness metric” and appointments set an “engagement” metric. The ratio of “aware” to “engaged” is a key factor in building a budgetary model.

- Expected awareness

- Expected engagement

- Number of ‘engaged’ persons

Sales Metrics

Sales metrics describe the bottom of the funnel. Using my inside sales example from above, with “appointments” as my engagement metric, number of “deals closed” would become my “percent of persons who become customers” metric. This “close ratio” helps me to understand the value of an “engaged” prospect.

- ‘Number of engaged’ persons

- Percent of persons who become customers

- Total expected customers

Customer information

Finally, I need to know how much each customer is worth. Low dollar, single-use customers are clearly less valuable than high-dollar, subscription customers. Recognizing that impacts how much I’m willing to spend to acquire that kind of customer.

- Average transactions/customer/time-frame

- Average profit/contribution/customer/time-frame

A Business Marketing Budget Example

Let’s imagine I want to run a Facebook campaign with the following assumptions:

- $200 budgetary allotment

- Product retails for $19.99

- Product costs me $6.00, so

- Gross profit is $13.99.

I know this is a SUPER inflated margin, I had actually configured the model for something else, but started making the video above and didn’t want to make it more confusing by changing a lot of values. After all, the numbers matter less than the principles.

Imagine I expect my ad to be generate 8,000 impressions (awareness metric) and I expect 2% (engagement metric) of them to click onto a page that they can choose to become a customer. So that’s 160 engaged prospect.

Imagine then, that of those 160 people, my website converts 5% into customers.

That means 8 new customers. Given my $200 budget, I spent $25 to acquire each customer ($200 / 8 customers). If each customer only buys once, on average (e.g., I don’t have a good mechanism for generating repeat sales), then this campaign will lose $11.03/customer ($13.97 gross profit – $25.00 cost to acquire the customer).

However, if I have a good mechanism for getting those customers to buy 4 times a year, then my customer value jumps to $55.88 ($13.97/unit * 4 sales) and that same $200 actually made $30.88 per customer ($55.88 total sales – $25.00 cost to acquire).

How times have changed

How times have changed since John Wanamaker’s lament that he doesn’t know “which half” is wasted. For most businesses, it’s possible using spreadsheets, CRMs, Google Analytics, and a suite of tools to know many of these metrics. Especially price, margin, and customer value.While this level of precision is less important for businesses that spit out cash or require more of a “time vs. money investment” (e.g,. BNI, Chamber memberships), thinking through the marketing with this framework can be hugely helpful in making sure the 4 key resources are well-allocated.

ProTip #6: Plan to lose, before you win

Before engaging in any campaign, set aside some “risk capital.” Most channels requires some learning before it can become profitable. For example, when I was doing a lot of “Morning Blend” appearances, I learned that channel worked best when used in conjunction with a good content plan. If I relied on it simply as a segment that aired once a month, it wasn’t very valuable (in my framework, for my immediate goals). But, as part of my evergreen content campaign, it’s actually ok.

But I had to learn that after doing it for a few months.

Treating your initial budget as “risk capital” within a model like the one mentioned above allows you to bound your risks, so you know when something isn’t working or where it’s broken. For instance, knowing that the Morning Blend was useful for my content campaign made it easy for me to decide how much I wanted to continue investing in it once our focus shifted from content to product.

Because campaigns are brittle – they could be working or broken on any of the dimensions mentioned above – setting aside risk capital let’s you ‘test the waters’ before commiting. In my experience, for most channels, it’s hard to learn for less $3k-$5k. For cash-strapped businesses, risk capital can be risky. Which is why it’s important to know your numbers. Especially your breakeven cost for customer acquisition.

If you exceed that threshold, kill the campaign. Learning over.

Make some real changes before you invest more in the channel or campaign.

ProTip #7. Monitor & Adapt

Finally, you want to make sure that you’re monitoring and adapting to circumstances. Most campaigns are going to require tweaking. This is especially true for online campaigns, where you can measure customer fickleness.

They also have a much steeper learning curve than most people appreciate. Just because “anyone” can “set up” a campaign, doesn’t mean they can make it profitable. A lot of factors go into making a campaign successful.

Having a budgetary framework that models results systematically makes it much easier to know where a campaign is broken. As you’re running a campaign, watch your cost of customer acquisition and pay attention to how people actually interact vs. your expectations.

Prepare for disappointment.

I’ve had ads I put together that I loved that did zilch. Zero. Nada. Laid big, fat, goose eggs.

And crappy ones I just threw up that did ok.

The difference? Who knows.

But because I have a model that keeps me honest in spite of my emotional attachments, I don’t generally over-extend too much on any given campaign.

For digital marketing, I use the following rules of the thumb:

- High impressions, low clicks = poor ad or poor offer. You’re probably over-spending. Go back to your model. Prepare to cut off the campaign.

- Low impressions, high clicks = poor ad, good offer. Pause the campaign, rework the ad.

- Low impressions, low clicks = poor audience. Try again.

- High clicks, low conversions = good offer, poor execution. Good work communicating the value on another channel. Fix your landing page.

Of course, there are times when these rules of thumb don’t hold true. And, for different channels, the thumbs are different. That’s why it’s important to know your various engagement metrics and have an (almost) algorithmic approach to your marketing budget.

If putting together a marketing budget stresses you with uncertainty, there’s a good chance you’re relying more on your gut than math. Don’t launch the campaign. Analyze the channel. Get clear on it’s purpose and your goals. Model it out. Bound your risk. Then test, small and repeat.

Your bank account will thank you for it.